Eliza (1834-1905)

James (1834-1905)

Osbourne (1837-1893)

Llewellin (1840-1910)

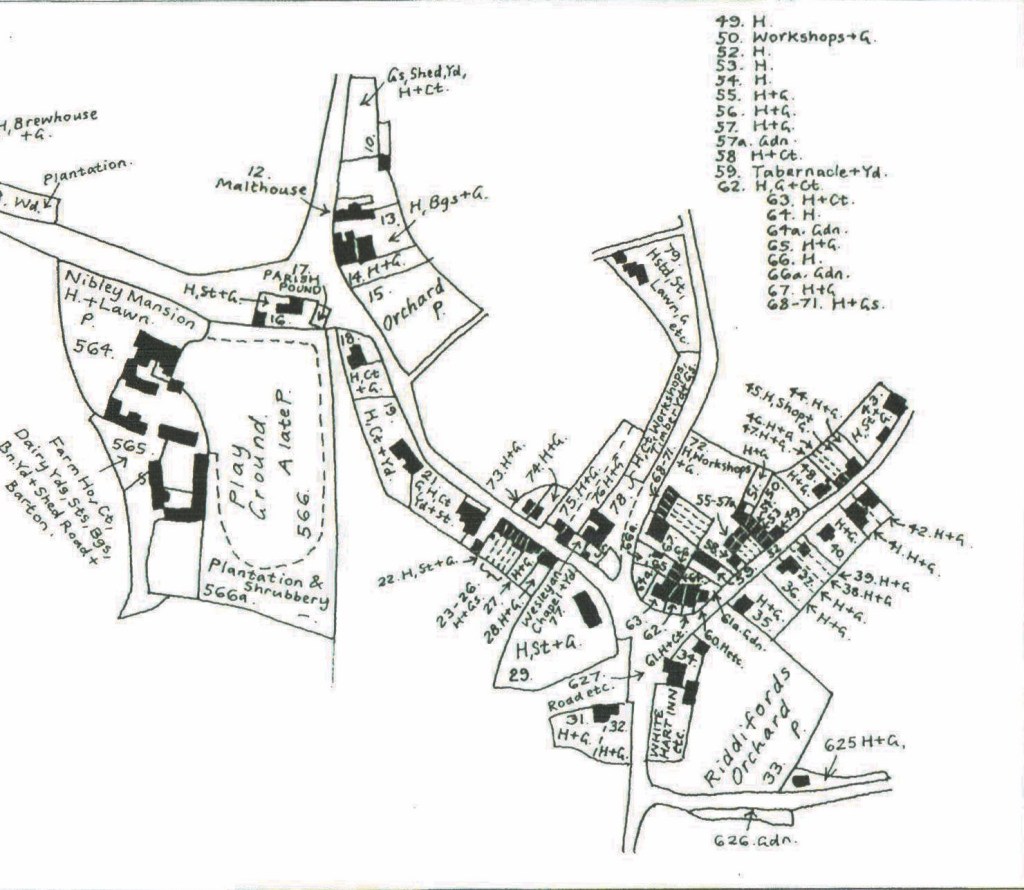

The Webb family – Henry and Lucy, with their eight children (five more were to follow) lived at the Square in Nibley Village, in number 55 (where Tyndale Close now stands)

Reproduced with the kind permission of Geoff Gwatkin, see Sources

Henry was a labourer, and sometime gardener. In 1851, there were still six children living at home, though James was apprenticed to Edward Knight and living at the Angel in Wotton under Edge. Osbourne, aged 13, was listed as a haulier.

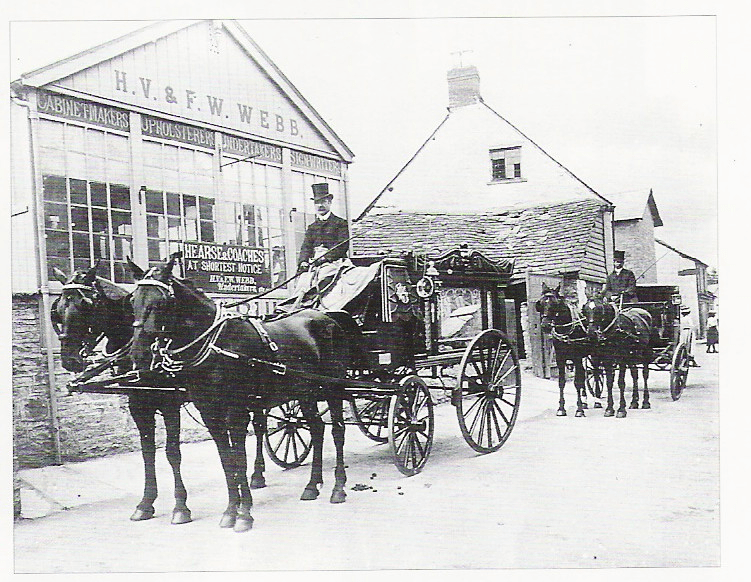

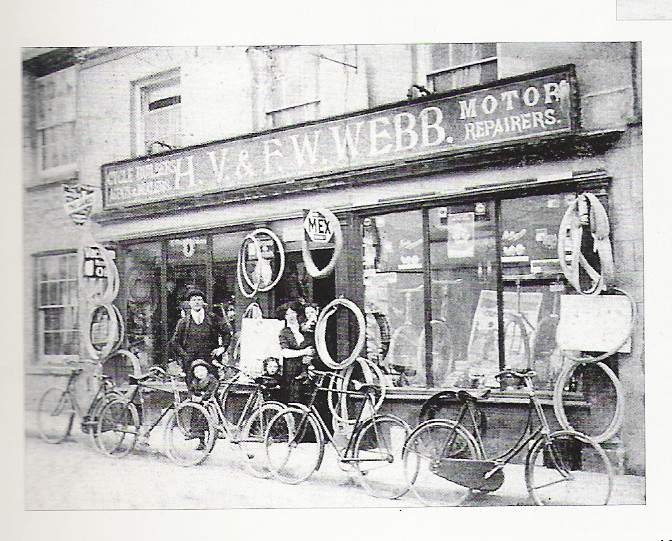

A local history book states that ‘A prominent business family name during the 19th and 20th centuries was Webb. The founder of the firm was a James Webb who arrived in Hay during the 1870’s (sic) to work as a stonemason in the town. Within a few years he had set up a carriage building and undertaking business in an old building situated in Church St. The company expanded and was eventually taken over by his two sons. They then built a workshop in Lion Street. They also opened a retail shop at 3 Lion Shop, specialising in the sale and repair of cycles, shown in the lower picture. Mr H V Webb is stood on the left.

In 1855, aged 21, James married Susan Price in Hay, where he lived for the rest of his life. The couple had ten children, and James left an estate worth £1090 when he died in 1906. He had been listed variously as a carpenter, a builder, a wheelwright and a carriage builder.

Photographs of James’ business, presumably after they had been taken over by his sons Humphrey and Frank.

Eliza married Joseph Murch in the 1850s. I have found no record of the marriage, but enough other facts ‘fit’ to make me thinks this is the case. Joseph was a widowed gardener. In 1861, Joseph, Eliza, Charlotte (Joseph’s daughter) and Joseph’s niece were living in Tormonham, Devon. This sounds unfamiliar, but in 1876, the name was changed to Torquay.

In 1871, the couple had three children, and Joseph had become a cab proprietor. Joseph died in 1885, from poisoning.

Torquay Times, and South Devon Advertiser 23rd January 1885

The Torquay Poisoning Case

An inquest was held …touching the death of Mr Joseph Murch, aged 63, cab proprietor, Underwood Cottage, who, as reported last week, from the effects of poisoning – The first witness called was Mrs Murch, who deposed her husband had for some time been suffering from palsy. On Tuesday about noon she was called by her daughter into his room and found him vomiting very much. She asked him what was the matter, and he replied that he had taken the wrong medicine. She looked round and found that he had been drinking from a bottle containing a poisonous lotion. She sent for the doctor immediately. Deceased had appeared very feeble that morning. Occasionally he had fits of dizziness, and after eating his sight was somewhat defective.- Dr Richardson stated that had been in the habit of attending the deceased, and on Monday ordered him a lotion composed of one ounce of liniment of aconite, and one ounce of liniment of belladonna. Deceased was a sufferer from what was know as trembling palsy. Witness saw him on Tuesday afternoon when he was suffering from the effects of poisoning…

The article continues at great length, but the conclusion was that Joseph had taken the poison in error.

The widowed Eliza, now a cab proprietor herself, was living with her son Frederick (recorded as a cab driver) at Underwood Cottage.

She was living in Plymouth when she died, in 1905, leaving £27.

Osbourne had an ‘interesting’ life, with a lot of brushes with the law.

He married Ellen Griffiths in St James Church, Bristol, in 1857. In 1861, they were living in Paul Street, Bristol, with their first daughter, Josephine. Osbourne was recorded as being a pastry cook. In 1871, the family (now with six children) were living in Nelson Street, Chepstow. Osbourne was a baker and confectioner, and Ellen was a shopkeeper.

A few years later, Osbourne, and his brother in law Charles Griffiths, were in trouble from the police.

From the Monmouthshire Beacon, 3rd December 1864.

Serious Charge – Osbourn Webb, of Chepstow, baker, and Charles Griffiths, his brother-in-law, with charged with having stolen a silver watch, of the value of £5, from Simon Murray, who deposed – On 24th of this month I got into a railway carriage at Bristol on the South Wales Union Railway. The two prisoners were in the same carriage with me (a third class). When I got in I had the silver watch now produced. The chain was round my neck, and the watch in one of my pockets. ..I was sober when I got in the carriage. After the train had started one of the prisoners gave me some rum out of a bottle. I drank three or four times and I became drunk. One prisoner was sitting opposite me, the other near me. I recollect nothing until someone called my attention to my loose watch chain. I then missed my watch.

The narrative continues to say that the watch was found in Griffith’s pocket. The two prisoners were committed to trial at the next Quarter Sessions at Usk.

At the Assizes, the prisoners claimed that they had been given the watch ‘the learned counsel for the defence addressed the jury, urging that the case against the prisoner Webb was so weak that they could have no hesitation in aquitting him. He dwelt strongly on the position of Webb, who, it was stated, was a respectable grocer in Chepstow, and concerning whom the policement expressed his surprise that such a charge should be brought.

One of the grand jurors gave Webb the highest testamonials of character, and documentary of a like character was also sent in.

The jury, after deliberating for about 20 minutes, returned a verdict against Griffiths of guilty, and against Webb of being ‘concerned in the theft’ which was afterwards amended to guilty.

The learned Chairman, in passing sentence, dwelt upon the good character which both had received; and said that there had been a false colouring to Webb’s position – he was not a grocer, but a grocer’s boy; and his master had sent a note to say if he was convicted he should again take him into his employ. Sentence : Webb (who had been recommended to mercy by the jury to four month’s hard labour; Griffiths, six month’s hard labour.’

In 1866, he was accused, but acquitted, of embezzling from his boss.

In 1872, the death of John Aukland, the couple’s 3 month old son was reported in the local paper. The mother had given the child doses of magnesia, as well as boiled bread to eat, which the jury judged was the cause of death.

In 1873, Osbourne (alias Osbourne William) was imprisoned for 6 months hard labour on a charge of embezzlement before being convicted of ‘stealing certain monies, the property of John Morgan, at Penarth’

Also that year, Osbourne had been charged with taking a lead pump and boiler, value at £1, from the property of the Duke of Beaufort. The defendant stated that the Dukes agent had instructed him to remove all items that stood in the way of any work he was doing on the premises. The case was dismissed for want of conclusive evidence.

By 1881, the family had moved to Miskin Road, Ystradfogwyg, Tonypandy. In all, they couple had seven children. Ellen died in 1884 and ten years later, the widowed Osbourne was living with 2 of his daughters, in the same place.

In 1887, he was fined £1 for stealing coal from a tip belonging to the Llwynypia Colliery Company.

Osbourne died in 1893, aged 56.

A modern-day picture of a house in Miskin Road

Llewellin Married Mary Reece, in 1860 in Cardiff.

In 1861, the couple were living with their infant son, Edwin. Also in the household was the 4 year old Mary Ann Reece, a ‘nurse girl’. Perhaps the illegitimate child of Mary, but I can’t find a baptism certificate so prove this.

In 1871, the family (joined by 2 more children) were living at Davies Court, Cardiff. Llewellin was recorded as being a labourer.

In 1881, Llewellin had become an iron dealer, and the family (with 4 children, a servant, and a lodger) were at Lower Cathedral Road. It the next census, Llewellin had become a dealer in old iron, and his eldest son, Edwin, was working in the same company. However, in 1901, at the same address, Llewellin was listed as ‘living on his own means’ while Edwin was a general labourer.

But Llewellyn had another string to his bow, as seen below.

From the Western Mail, 17th April 1900

Llewellyn Webb, The Street Preacher

Man of the Strongest Lungs in Town

Career of Curious Experiences

One Sunday night, as I strolled down the ?yes, not unlike that of a caged lion, coming from the direction of the Penarth Road, somewhat alarmed me. Scanning the canal bank for this Cardiff example of the Felis nobalis, I found near the Bute Monument a big crowd – say two or three hundred – and which included W E Pocock (?orist), W M Davies (solicitor), Widdy Widdy and other local notabilities, circling about a ?ng from which the roars, now much resembling a human voice, proceeded.

Llewellyn Webb was the circus. He was walking ‘to and fro in the earth’ – thumb-blackened Bible in hand, racking his memory, as it seemed, for savoury adjectives of comnatory import with success, for the language out was of a kind one never hears in chapel. Webb was denouncing the ‘Cainites’ – an old-world race who had, it seems. Particularly diabolical characteristics. ‘Cainites’ were the ‘giants’ referred to in the book of Genesis as the offspring of the Sons of God – that is, demons – and the daughters of men – the posterity of Adam and Eve. How the sweethearting was conducted between these demons, who were spiritual beings, and their particular friends, the women of the period, is not clear, and Llewellyn Webb, in a subsequent conversation, admitted that it was a mystery even to him, which is saying much.

However, the Cainites were all drowned in the great flood – an utterly fortunate thing for the future of the world, in Webb’s opinion, and in ours, too, if the Cainites were a quarter a wicked as Webb says they were- on the ‘thor-r-ity of God’s word!’ But what ‘copy’ they must have made for the newspapers of that period!

The Cainites all drowned and duly anathemised, after a passing curse on modern Spiritualism – or ‘Spiritism’ as he prefers to call it – Llewellyn Webb got down to the county council and the duty of Christians as to elections.

‘I ca-a-a-n’t vote’ the orator explained, with a roar that, in the stillness of that Sabbath evening, could not but have travelled as far as St John’s Church, in the one direction, and the Cardiff Castle, the gaol, or the Grangetown gasworks in others.

He could not vote or join anything. Nor could rightly any Christian. ‘It were just these ‘malgamations and ‘sociations’, Mr Webb went on to say, that caused all evils. Believers went into partnership with unbelievers, connected themselves with political parties, and ‘here was the Liberals praying to get the Liberals in, and the Conservatives praying to get the Conservatives in, and God’s hands was tied!’

Webb’s meeting are conducted without any order, and at this point he called to his side a brother, who bore a little lamp, by the faint glare of which the orator proceeded to give to his audience ‘A Scripture’, that is, reading from the Bible, interpolated at intervals with quite unconvential outbursts of exposition. In one of these, dealing with Christian work, he told of how he himself put in spare moments footing orange peel from the pavements, suiting the action to the word, for Webb is nothing if not dramatic.

‘That’s Christian work – not prayin’, an’ singin’ and preachin’, and taking up collections and pew-rents, an’ preachers goin’ to college, and holdin’ up Wesleyanism an’ Indepentism, and Churchism, an’ Salvation Armyism – oh my God! Have mercy on us!’ Webb proceeded growing more desperate every minute.

This led him to a terrible denunciation of ‘religionism’ which he boldly declared ‘was not of God’!

‘Accept Christ, young men! Don’t be religious, for Go-od’s sake!’ and, having followed this rugged path of general denunciation for some ten minutes, Webb abruptly collapsed.

‘Good night! I be an old man!’ he said as he gouged a passage through the startled throng, Then, as is by sudden inspiration, he returned, beat for himself a smaller circle, and let off this dynamite blast:-

‘Accept Christ! Accept Christ! And be always young! Don’t be religious! Good-night, good-night!’ and as the eccentric evangelist made for St Mary-street the crowd partly followed, for all the world like the tail of a comet, with Webb for nucleus!

…….

I met Llewellyn Webb outside the town library, and asked if he could give me half-an-hour’s chat?

‘Is it a soul matter, my friend?’

‘It is a serious matter.’

‘But what I want to know is – are you a child of God or a child of the devil?’ (What a question to put to a journalist!)

‘How you would class me I cannot say’, said I

Webb drew back several paces, and struck an attitude. Instinctively I knew a reverberation was coming, and held on tight!

‘I da-a-a-a-re not class you!’ he roared, ‘God’s word says. ‘He that believeth HATH’. A man comes to me, and he says ‘Oh yes, Mr Webb, I believe in the Lord Jesus Christ: I am saved’. I say’ ‘Praise Godd, brother’. Give me your hand, and we hold sweet communion together. But that’s beside the question; what is it you wanted?’

I explained my mission, and we sauntered down between the orange trucks discussing the political problem of why Christians should not vote, and this is how Llewellyn Webb figured it out.

Every Christian belongs to the ‘Israel of God’ – the ‘Church of Christ’. He is called ‘out of’ (with a right hand pendulum action) and ‘into’ (with a left hand ditto)- ‘out of the world and into the Church, which is His body’! The Government of the world is in the hands of the ‘Gentiles’ and the ‘Church of God’ had no concern in it – not ‘during this dispensation’. In the Millennium Christians would ;judge the earth’. But before that, there would be a time of seriousness. ‘The beast and the false prophet’, leaders of religious armies would have a religious war until ‘there’ll be blood up to the horses’ bridles by the space of 3000 furlongs – 200 miles! The n God – mind you get that – will cast down the beast and the false prophet down into hell alive – you’ll see it in Revelation!’

‘No doubt about the literal interpretation of all this?’ I queried.

‘Absolutely no doubt!’ exclaimed Webb, with steam-hammer emphasis, ‘God’s Word says it!’

Nibley House when Llewellyn Webb came into possession of it, eighteen years ago, was in a field, and solitary. It is now an integral part of Lower-Cathedral-road, in the centre of a thickly-populated district, though, as is fitting, it maintains a certain character of it’s own, and is not quite like its plebian neighbours.

Nibley House is so named from it’s owner’s birthplace, the little village of North Nibley, in Gloucestershire. It was on Nibley Knoll, where stands a lofty column to the memory of Tyndale, Bible translator, saint, and martyr, that Llewellyn Webb, at the age of nine, began life’s mission by minding sheep. Even in those years of juvenility the ruling passion was active, for little Llewellyn got together his sheep for a congregation, and from an improvised pulpit of rock thundered forth exortation and warning.

Little Llewellyn when he could scarcely toddle began to grow pale and thin. He had been a robust little chap, with plenty of colour. A wise and solemn doctor diagnosed the case, and pronounced the child’s doom, He was evidently consumptive, and the poor mother was told she would lose her boy, Nobody, however, felt more tired than that doctor when, a month later, boy and mother appeared again – boy ruddy as ever, mother wanted to explain.

It was a case of pickled onions. Little Llewellyn, unobserved, had been dipping his fingers, not wisely but too well, into his mother’s pickles, and when these were removed out of reach the boy’s colour returned. Moral:- Put not your trust in doctors!

Mr Webb’s father was a gardener, and both father and mother, it seems, were good Churchpeople, until one day a ‘Gipsy Smith’ of the period turned up at the little Independent chapel. Father and mother got ‘converted’ and forwith aroused the antagonism of the local clergyman by holding prayer meetings in their house. This individual was down on schism of every kind and decree. He ‘wouldn’t have no mixed breed’ he said. He refused to allow the children any longer to attend his school, and even threatened to ‘root out’ one who had been laid in the churchyard! This refusal meant, too, more than appeared on the surface, for by a local charity one or two of the family would have been entitled to a considerable sum of money on leaving school for apprenticeship etc.

So the older ones were sent out into the world – Llewellyn to mind sheep on Nibley Knoll and after that he got to be a coachman.

And Webb might have been a coachman all his life, but he had an ‘extraordinary mother’ and she used to pray for her lad so vociferously, and, what made things worse, Webb’s master ‘had a horse, and he did very often kick, and upset the carriage and turn ‘em all out into the ditch’ – so much so that it was decided to get rid of him. Llewellyn, in reply to inquiries of any prospective customer, was, of course, instructed to say the horse was ‘quiet and docile, easy to ride and drive’ etc. He mentioned this to at home, but his mother, finding these little business fictions inconsistent with her Christian convictions, prayed more and more – ‘Lord, save my boy from telling lies!’

Llewellyn Webb concluded to run away. On a Sunday evening, after a home visit, he asked for his wages then due, because ‘my mother and father ain’t well off, sir!’

The request was innocently granted. At three o’clock the next morning our hero, now a strong youth of eighteen, started for Wales, with a bundle of clothes under his arm. It was like him to strike a bee-line, over hedges and ditches, for Wickwar Station, where he caught the six o’clock train to Bristol. At Bristol he inquired the way to Wales, and they directed him to the Cardiff and Bristol boats.

Arrived in Cardiff, he walked up Bute-road. In the window of the Golden Key Grocery he saw this notice:-

A BIG BOY WANTED

‘Thinks I – I be a big boy; so in I goes’

‘Where are you from?’

‘From Gloucestershire’

‘When did you come to Cardiff?’

‘I come to-day, zir.’

‘Have you got a character?’

‘No zir; I never wanted one.’

‘What do you want a week?’.

‘What’ll you give me, zir?’

Llewellyn Webb was taken on at a salary 7s a week. But not for long. A friend told him that on the docks he could earn a pound a week, and 30s if he put in overtime. So he abandoned the grocery business, and became a docker. He now got 3s 9d a day, and by working Saturday afternoons and Sunday nights ran wages up to the princely sum of 30s a week.

Then he wrote home to his mother:-

‘Mother,-I wouldn’t tell lies, and will send you 10s a week’.

Two years later an evangelist ‘preached the Gospel of the Grace of God on a heap of stones where the Stuart Hall now stands’. Llewellyn attended the meeting, and, he says ‘I believed God there and then, and was saved on a Saturday evening’. Without going to college, Llewellyn Webb began to preach to the navvies. ‘I ‘ould go into courts and old houses, and talk about Christ, and how He had saved me’.

Sometimes, on Sundays, he made incursions on his own into the country, munching bread and cheese, and drinking water from roadside springs, everywhere reading the Bible, and preaching. Some threw mud at him. But that didn’t matter; others said ‘God bless you, sir’. Thus did Webb for years.

His difference with the Baptists at Bethany, with whom he had first associated, was this – that children of God had command to go out but not to go in, to preach the Gospel. Another point was that sermons ought not to be ‘got up’ so much as ‘got down!’

In truth, the sympathetic, impartial onlooker sees soon that the hero of our tale was too intensely Christian to have his worship confined to the respectable atmosphere of a church. He took up with a couple of kindred spirits – Mr George Smart and Mrs Hollyer – and for eleven years these faithful Bohemians paraded Butetown every evening and all day Sunday. Butetown was then even less civilised than now. Exciting incidents were the order of the day. In Whitmore-lane (now Custom-House-street) resided the notorious Butetown bully – Jack Matthews. He ran an establishment that was particularly dusky in character. Just there was the missionaries’ pitch and ‘out comes a girl one day as we was preachin’ and said ‘Will you come in and see my mother – my poor mother’s dyin’, and wants you to pray for her!’ Well, I goes in to pray-‘

But, instead of one dying woman, the poor unfortunate young preacher, on getting upstairs, found himself surrounded by two or three women – very much alive-and with absolutely no costume except that supplied by nature!

On another occasion a sailor rushed out of here. He had a trousers on, but nothing else! Webb took off and gave it to him!

Exciting times! I should say so! Abandoned characters from public-houses and dancing salons used to be watching for the Gospel distributor with rotten eggs, snuff, ashes, cabbage leaves and dirty language. Often they were belaboured with ‘cabbage bones’ and the contents of vessels I dare not particularise were thrown amongst them for what the Welsh, I believe, call ‘gwagiad’ were among the favourite weapons directed against these faithful ministers of Christ. ‘They’d as soon dip you into the dock as look – they was devils in those days, I tell you sir!’ explained My Webb to his innocent interlocutor – a child of civilisation!

Many poor girls down on their luck were saved by the missioners from a life of sin. They always kept a kettle boiling at the Gospel-hall, which they afterwards got the use of, and women especially were invited to tea. Webb himself took in one girl who had been robbed of £14, and so had been afraid to go home. Through the kindness of Mrs Hollyer and the mercy of God she got converted, and afterwards astonished the night meeting by rushing up to Llewellyn Webb, putting her arms around his neck, and plentifully kissing him!

‘This is the man who saved me,’ she exclaimed ‘when I was on the road to hell!’

For forty years, save for a period of illness, twelve years ago, Webb has not missed a Sunday night’s preaching.

‘If the snow’s up to my neck, I’d go out’ says he.

Passers along the lower end of St Mary-street often hear Webb roaring away in the middle of a blinding storm of wind and rain, to a few stalwarts crouched in doorways in the Central Hotel-crescent, and in tones that give elemental natural noises no chance.

‘Tell ‘em’ said Webb, as I sat one afternoon in the well-furnished front parlour of Nibley House – ‘tell ‘em these people in churches and chapels do tell lies by millions!’

[several paragraphs omitted]

Webb has never accepted a penny for preaching in his life. From 1877 to 1891 he was in business, and in the earlier of those years managed to secure a corner in old iron, which, from being practically valueless went up to £6 10s a ton or, as Webb puts it ‘God blessed me in the past, so that I’ve never wanted in this life’

‘Oh, ‘twas beautiful’, he added; ‘you could make as much as you liked in Cardiff then!’

Not that he was a speculator alone, for Webb claims to have himself carried more tons of iron than any other man in Cardiff. They called him ‘the Cardiff devil’ and sometime ‘ the Cardiff striker’ both for his feats of strength and his vigorous attacks on ‘religion’ and irreligion alike!

‘Great credit’ Mr Webb says, ‘is due to his wife, his senior by seven years, who during forty years of Married life has been to Webb both wife and mother.

Another view of Llewellyn’s character is demonstrated below

Western Mail, 31st March 1900

Those landlords who have difficulty securing their rent may take a leaf out of the book of Mr Llewellyn Webb, Cardiff street preacher, who always kicks orange peel off the pavement. Mr Webb’s money is invested in house property, and he follows John Ruskin in humanitarian treatment of tenants. Mr Webb gives a remarkable instance of, as he puts it, the way ‘God looks after his children when they honour Him. One of his tenants was ill – ill for a long while, and no rent was forthcoming. Mr Webb used to make a friendly call about once a month, but never asked for rent. ‘I am a child of God, and I know you can’t pay, and I can’t turn you out’. Was his curiously foreign way of arguing when the tenant himself expressed regret at the arrears that were accumulating. Presently all at once the tenant got well, but not until the rent unpaid amounted to £32 10s. He went to sea, and shortly after, strangely enough, came into the possession of some £540. One day a messenger was sent asking Mr Webb to come down. The preacher called, and at the door deprecated the lady’s anxiety about the rent ‘ I have never asked you for it, have I?’ said he. But she took Mr Webb by the arm and led him into the front parlour, where a bag of sovereigns lay on the table, from which her husband, with radiant countenance, proceeded to count 32! Even then Mr Webb refused to accept the money until he was assured both that it had been come by honestly, and that no such thing as a ‘mortgage on the furniture’ had been made.

Various adverts show that Llewellyn owned several properties, including ‘several detached cottages, freehold, near Tyndale’s Monument (from a sales advert of 1895)

Llewellin died in 1910, aged 70, leaving £1659. His bequests were as follows:

- to his daughter Emma, £50 and ‘the house I now live in’ i.e. 34 Lower Cathedral Rd, Cardiff.

- to his son Llewellyn, £50 and my freehold house at 22 St Johns Crescent, Canton, Cardiff.

- to his son John Henry Webb the ‘leasehold, yard, workshops and offices now in the occupation of the postmaster as telegraph stores and known as 32 Lower Cathedral Road.

- to his trustee [Charles Edward Garfield, of Lower Cathedral Rd] the leasehold house and premises known as 29 Mark Street, Cardiff, ‘upon trust to pay the income thereof to my son Edwin Webb, and on his death’ sell it and divide the proceeds between my daughter Emma Bell, the daughter of ‘my said daughter Emma’ and my grandaughter Kate Mary, the daughter of ‘my son John Henry’.